Democracy Without Elections

Could this constitution for a settlement on Mars help us forge a brighter future for democracy?

Welcome to New World Same Humans, a weekly newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and you haven’t yet subscribed, then join 17,000+ curious souls on a mission to build a better shared future 🚀🔮

🎧 If you’d prefer to listen to this week’s instalment, go here for the audio version of Democracy Without Elections. 🎧

Yale political theorist Hélène Landemore made waves on Twitter recently when she published a constitution for an imaginary human settlement on Mars.

At the heart of the document is a powerful idea; one that Landemore says could revitalise our ailing democracies.

So this week, reflections inspired by that: on the states we’re in now, and how Landemore’s system might just be the answer.

In 1992, the science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson published Red Mars. The novel – the first in the now iconic Mars Trilogy – sees 100 colonists travel to the Red Planet to establish a new human civilisation.

The hundred grapple with a series of technical challenges, including the need to terraform the Martian surface. But another, more abstract question also runs through the book: should their new civilisation be subject to the traditions and governance structures of Earth? Or should the colonists seize their chance to sweep all that away, and start again?

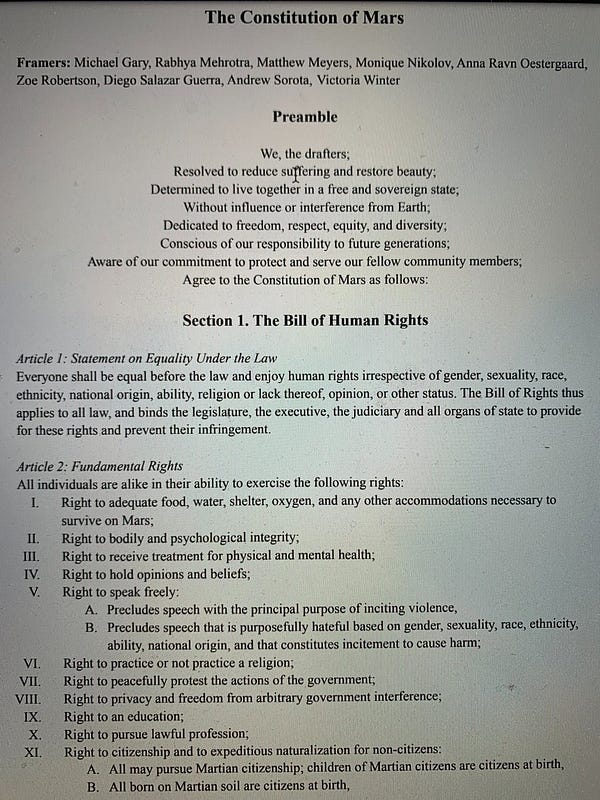

Yale political theorist Hélène Landemore asked her students to read Red Mars this semester. That’s because she had an unusual task in mind for them; she wanted them to write a constitution for an imaginary Martian society. They complied, and last week Landemore shared the results.

The quest to create the ideal constitution – the perfect ground rules for a human collective – is a central theme in political philosophy. One that runs through Plato’s Republic all the way to John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice, which famously attempted to ground liberalism in an ‘original position’.

At the heart of the Landemore Constitution, though, is a specific idea. It’s one that she persuasively argues could revitalise democracy for the 21st-century. And it could also transform our ability to take collective action for the good of the long-term future.

Dive into the constitution, and you’ll quickly see the central idea take shape. At first everything is recognisable; Landemore’s students want their new civilisation to be a democracy, underpinned by a charter of human rights. But this democracy won’t be shaped by the regular drumbeat of elections, as ours are. Instead, it will be governed by mini-publics; assemblies of 250 adult individuals chosen every two years via stratified random sampling.

Six mini-publics – on Foreign Policy and Earth and Interstellar Relations, Social Policy and Welfare, Environmental Policy, Economic Policy, Civil Rights, and Governmental Oversight – will make up the legislature. And each mini-public will send 50 of its members, also chosen at random, to a Central Chamber, which forms the executive.

In other words, in this Martian society you don’t vote for your representatives. You are a representative, and you’re represented in turn.

The idea, of course, isn’t new. It’s the way the ancient Greeks practised democracy. Our system, in which we vote for those who will represent us, is much newer.

It’s hardly news that this system is, right now, more than a little creaky. And crucially, Landemore argues that the kind of direct democracy outlined in her Martian constitution could be the answer. Landemore calls this system open democracy, and it’s the subject of a book she’s just published under that name.

*

So why could open democracy be better than what we have now?

In short, our form of representative democracy is a closed, gatekept system in a world increasingly intolerant of anything of the sort. Theory has it that anyone can stand for election. But in practice our representatives are drawn overwhelmingly from a small, self-replicating elite class.

Long-running trends – rising affluence, the demise of social deference, the rise of an assertive equality – make that kind of elite dominance anachronistic. And in a 21st-century, connected world, it can feel positively archaic. In 2021, many balk at the very idea of choosing people who know better to make decisions on their behalf. At the heart of what ails our system is a growing tension: between societies dominated by elites, even as they become certain that elites should not exist.

The results are manifold. Bad governance, by an out-of-touch political class determined to preserve its special status. And widespread disaffection that curdles our political culture, and sends voters towards populist candidates who make empty promises to smash the system.

Open democracy, says Landemore, could change all this. Here, everyone is a representative in waiting. Sure, you might not be in the legislature right now. But those who currently govern are ordinary people, just like you. And soon enough your turn may come.

It’s a persuasive idea. The online revolution has turned us all into Sovereign Individuals, empowered to know anything, communicate with anyone, and represent ourselves in the massive, networked public squares that are Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. That has transformed the texture, and the mechanics, of our collective lives across the last two decades. And it’s conditioned people to expect participation. A shift to open democracy would align our political system much more closely with the expectations generated by a connected world.

There’s another reason why the NWSH community should take an interest in Landemore’s idea.

I’ve written before on how our political system stymies effective planning for the long-term future. The idea that people simply don’t care about what will happen once they’re gone isn’t true; evidence points to idea that most people do care. But that aspect of our shared nature is short-circuited by the electoral system, which incentivises politicians to think no further than the next election.

In a system of open democracy, those chosen to serve in government will have no elections to worry about. They’ll be liberated to act on the shared moral intuition that we shouldn’t ruin this world for the generations that will come after us.

I’m not naïve enough to believe that a shift to open democracy is in sight. The political challenges involved are huge; perhaps insurmountable. But if there’s one thing the last 14 months has demonstrated, it’s that epoch-making events always seem far off until they’re on top of us.

We’ve living inside a revolution that’s created radical new forms of networked power, and transformed the relationship between individuals the collective. If we can open our minds to it, open democracy may be just what we need.

A fine balance

Thanks for reading this week.

A sovereign state must always balance a vast range of competing forces. And across the last few years in some liberal democracies, that balance has looked precarious.

In the coming months and years, New World Same Humans will continue to investigate the future for liberal democracy and the nation state.

And there’s one thing you can do to help with that mission: share!

If this week’s instalment resonated with you, why not forward the email to someone who’d also enjoy it? Or share it across one of your social networks, with a note on why you found it valuable. Remember: the larger and more diverse the NWSH community becomes, the better for all of us.

I’ll be back on Wednesday with New Week Same Humans. Until then, be well,

David.