The Worlds to Come – Instalment One

Language, virtual realities, and our quest to be at home in the world.

Welcome to this essay from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on technology and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 20,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

🎧 Attention audio lovers! If you’d prefer to listen to this instalment, go here for a podcast version of The Worlds to Come – Instalment One. I’ll add this and subsequent instalments to Spotify and Apple Podcasts soon. 🎧

To Begin

I delayed this essay by a month, so on one level it feels great finally to publish it.

On a deeper level, though, I’m hitting send today with a high degree of trepidation. The Worlds to Come, which is the first in a new series of monthly essays, marks a departure for NWSH.

First, it kicks up by several notches my attempts to think philosophically about emerging technologies and what they mean for our shared future. There is, you know, actual philosophy in this essay. There are even some small attempts to do philosophy. Maybe that is unwise. Treat it as a form of thinking aloud.

Meanwhile, the essay has become long enough to be published in instalments. Below you’ll find Instalment One; the next will be with you in a few days.

Set against this trepidation, though, is an undeniable fact. It feels a risk to publish this, and yet I had to publish this.

The Worlds to Come marks a first attempt to articulate a set of ideas that have been troubling me for years. About systems of representation, virtual realities, and the way we understand our place in the world. The road ahead is undeniably bumpy. But for those willing to join me I can promise an eye-opening ride. And an authentic attempt to think through, as best I can, a network of submerged relationships that seem important to me, and that I haven’t seen anyone else try to articulate (yet).

Okay, enough preamble. Let’s get into it.

If you’d prefer to listen to this essay, just scroll up to see a link to the audio version.

Table of Contents

Introduction: On the Threshold

1. What We Have Forgotten. Humans, language, and being-in-the-world.

2. Cast Adrift. A brief history of the Gods we made, how we banished them, and where that left us.

3. Crossing Over. Virtual worlds and the leap back to enchantment.

4. Conclusion: Where Next?

Introduction: On the Threshold

(i)

To begin, a little origin story.

A lifetime ago now, my wife (back then, girlfriend) and I went to Venice. It was our first proper holiday together.

We arrived past midnight; the city was a gauzy darkness. In the morning I pulled back the curtains, and sunlight flooded into the tiny and absurdly expensive room that was our accommodation. Looking across the rooftops, neither of us could believe what had opened itself out in front of us. This city.

That morning, as we made our way through the byzantine alleyways and past one devastating gothic church after another, the feeling only intensified. By the early afternoon, we were ping-ponging a mantra back and forth. This place is unbelievable. It feels like being in a film.

Venice heaps beauty on top of beauty; the sense of the unreal that it engenders is familiar to any visitor. A million people and more have set foot in Venice and exclaimed: this is like a movie!

But on that trip, the phrase began to bother me. It’s a strange thing to say, isn’t it, that an experience you’re having, something in front of you now that you can see, hear, and taste, feels like a film? What does it mean? Why do we say it, and especially about experiences that feel particularly intense, significant, or spectacular? Shouldn’t those experiences feel, if anything, the most real to us? And yet somehow when we try to articulate them to ourselves, we reach over and again for the same comparison. We compare them to the fictional worlds we build. Not to real experiences, but to representations of experiences.

All this kept bothering me long after we’d come back to London. I came to think, in a tentative way, that this tendency to compare real life to fiction tapped into something far deeper about our relationship with representations.

It seemed to me that our systems of representation – films, novels, maybe even language itself – tended to become, in some powerful sense, more real to us than the experiences those representations were intended to describe. And that this fuelled a strange inversion. Instead of looking at our representations and saying, ‘this is just like a real experience’, we look at our real experiences and say ‘this is just like our representations’.

Life happened, as it does. But the thought never went away.

In the meantime, a new kind of representation has slowly been taking shape around us. It seems to be different, in an important way, from the other representational forms that we know. With virtual reality (VR) we discover representations that become worlds unto themselves. Not representations of the world, but representations-as-worlds.

All of this, it has long seemed to me, would be a useful line of thought to pursue. Maybe thinking deeply about prior systems of representation can help us better understand the nature of virtual realities. And maybe all this can cast new light on the opaque relationships between we humans, our representations, and reality (whatever we think that is).

This is the series of private reflections, such as it was, that brought me to this essay. But the work that follows travels a long way from these origins.

As philosophically naive as I was when I first started thinking about all this, even I knew that many others have pondered the ways in which way systems of representation seem to estrange us from our direct experience. This essay attempts to make use of, and in some small way build on, some of that thinking.

But the attempt I’ve made here is pretty much certain to be imperfect, and subject to revision. Which is to say that this essay doesn’t mark a conclusion, in any sense. It is only, and at last, a beginning.

(ii)

We live in a disenchanted world: children of God, adrift in the Godless universe we made. Our predicament is nihilism. We fear that our lives, and the world we inhabit, are meaningless.

But a technology is emerging that can change all this.

At the heart of this essay is a single idea: that our coming journey into virtual worlds can cause a transformation in our relationship with this world; one that can allow us to overcome nihilism, and again understand our lives as meaningful.

On first hearing, this claim seems impossibly far-fetched. If we want to interrogate it, we’re thrown into a thicket of further questions. What is the nature of virtual worlds, and how should we relate to them? In what sense do we no longer understand our lives as ultimately meaningful, and is it possible to recover the belief that they are? What is the difference between a virtual experience and a real one? Is there a difference?

I want to take aim at these questions. Specifically, I want to examine a set of more-or-less obscure relationships between virtual worlds, systems of representation, and meaning. My contention is that when these relationships are unpacked, virtual realities are shown to be the fullest realisation, or telos, of a certain orientation to the world: one that is mistaken, but that predominates among people who live inside modernity. And that because of this, our entry into virtual worlds can help us overcome that orientation, and discover one that is more authentic.

To believe this is to believe that the advent of virtual worlds is as significant as that of writing.

These are alarmingly big claims. Scepticism is warranted. Especially in light of the endless hype we’ve been served, recently, when it comes to VR.

*

There has been much talk of virtual worlds, or what some call the metaverse, across the last two years. Virtual realities, we’re told, are finally blooming into vibrant life. They will transform the way we work, entertain ourselves, and connect with one another.

Critics say that talk is just hype. They point out that today’s virtual worlds are clunky and unconvincing. And that the so-called metaverse is, in its current incarnation, a marketing strategy in the hands of Big Tech, which seeks only to insinuate itself ever deeper into our lives.

These criticisms are valid; the Silicon Valley hype train is infernal. So this essay will take for granted only two limited claims about VR, which most technologists regard as secure. First, that virtual worlds are not only a fad that will soon dwindle; that is, that developers will continue to create and refine virtual worlds, and at least some people will use them. Second, that the reproductive faithfulness of VR will continue to improve and bring us, soon enough, to the point where a certain suspension of disbelief is possible. Others go much further and say that VR worlds will eventually become indistinguishable from this one. That may be so, but the argument I want to make doesn’t depend on it.

Still, the idea that virtual worlds have anything to do with our beliefs about the ultimate meaning of our lives seems obscure. Crucially, it’s not my intention to argue that virtual worlds themselves will, in any simple way, resolve our quest for meaning. I don’t believe that we’re set to disappear into the metaverse, and live happily ever after. Instead, my interest lies in what virtual worlds can show us about this world, and our relationship to it.

The model I’ll build will hinge on a set of related arguments. At the heart of it, though, is a central idea: that virtual worlds are, in some deep sense, the end-point of a journey that began with language.

In Part 1 we’ll establish the inescapable connection between we humans and systems of representation. We’ll see how, starting with language, systems of representation serve a paradoxical double function. They crystalize the everyday world for us. But they also estrange us from a deeper underlying truth, which is the unity of ourselves with the world.

In Part 2 we’ll look at how this estrangement problematises our relationship to the world. And how, as such, it is at the root of nihilism. This is the idea that there is no ultimate meaning to our lives, or meaningful relationship between us and the world we find ourselves in.

In Part 3 we’ll see how virtual worlds are the telos of the human propensity for representation-making: in VR we see our representations of the world become representations-as-worlds. Put another way, virtual worlds are a hyper-projection of the subject/object metaphysical stance that is associated with language. In this way, they mark the fullest realisation of our journey through estrangement. That means they can propel us towards a revelatory leap: one that will see us discover a more authentic orientation to the world.

As it sounds, some of what will follow is a kind of genealogy: an esoteric theory of our spiritual history that owes much to a set of canonical thinkers. It will call on the Ferdinand de Saussure’s model of language as a system of difference, and Derrida’s revelation of the way that these systems render meaning unstable. Most of all it will call on Heidegger, and his revolutionary collapse of the subject/object distinction that lies at the heart of traditional western metaphysics.

The route we take to our destination will be a bit of a spiral. First, I’ll need to lay down some foundational ideas. We’ll need to clarify some terms. What do we mean by ‘the world’? What do we mean by ‘nihilism?’ With all that done, I can return to the ideas we’ve established and show how they relate, in ways not immediately obvious, to virtual worlds and our spiritual orientation to this world.

*

As I set about drafting this essay, the iconic philosopher of consciousness David Chalmers published a book about virtual reality and human meaning called Reality+. Chalmers is a brilliant philosopher; Reality+ is a compelling book. But this essay can be read as an argument against what is, on my reading, its strongest claim: that life inside a virtual world can be in itself as meaningful as life in what we call the everyday world.

My conviction is that this isn’t true. Instead, it seems to me that there’s a special relationship between ourselves, the world we find ourselves in now, and meaning.

Who (the hell) am I to argue with David Chalmers? The answer is: no one. I can offer no worthwhile reply to this question. Anyone who reads this essay and finds themselves intrigued by the questions it raises, and who wants to read a proper philosopher address those questions, should also read Reality+.

1. What We Have Forgotten

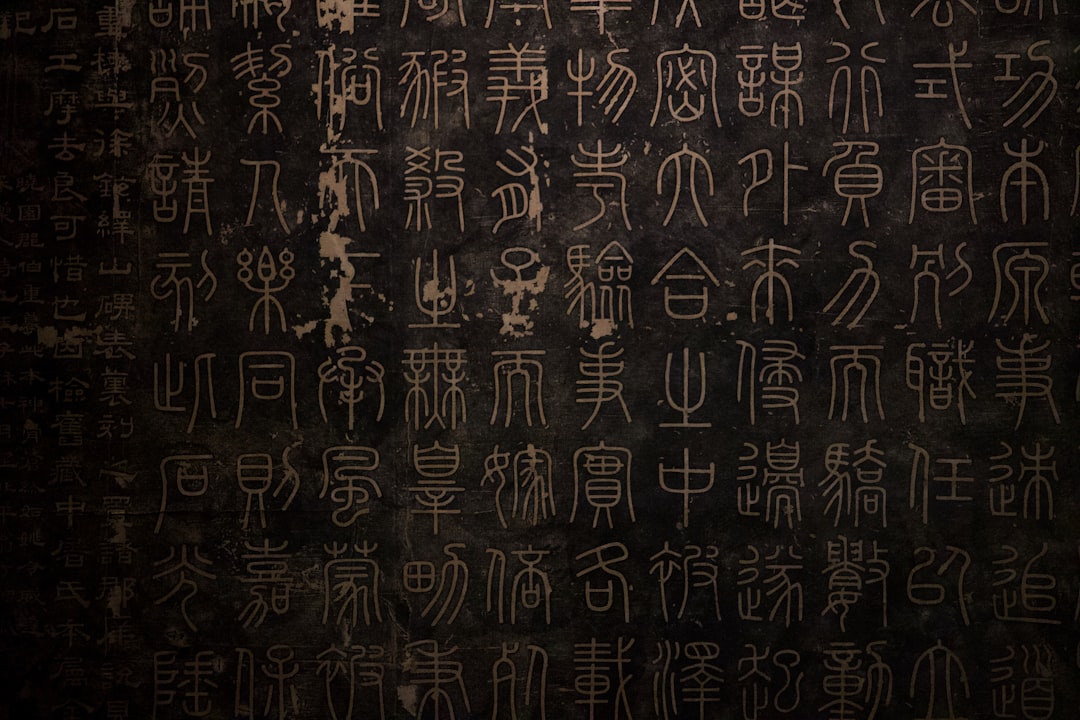

No longer in a merely physical universe, man lives in a symbolic universe. Language, myth, art, and religion are parts of this universe. They are the varied threads which weave the symbolic net, the tangled web of human experience.

Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man, 1944

*

We have a destination in our sights. It is to show that the emergence of virtual worlds can provoke a shift in our spiritual orientation to this world.

VR is a system of representation. In this section, I’ll rewind to the beginnings of our relationship with those systems — a relationship that starts with language. My argument will be founded in the work of one of the 20th-century’s most significant thinkers: the German philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Having laid these foundations, in Part 2 we’ll go on to look at the relationship between systems of representation and nihilism.

(i)

What is a human being?

One answer that stands at the foundations of a long tradition: we are the animal that uses language.

In the Nicomachean Ethics and elsewhere, Aristotle suggests that humans are the creature ‘with a rational soul’. He seems, though this interpretation is contested, to associate this with our capacity for language; zōon logon echon is the animal who seeks meaning, the animal that speaks.

There are good reasons to prefer the connection with language, rather than rationality, as the defining characteristic of the human. Sure, people can be rational. But what about our monumental unreason; isn’t that a uniquely human trait, too? No other creature on Earth uses trigonometry. But no other recites poetry, or commits acts of genocide. Our ability to use symbolic representations – to let one thing stand for another – underpins all that and more.

It should be no surprise, then, that an obsession with language is the thread that runs through so much 20th-century thought. There is, unsurprisingly, no agreement on the big questions: the relationship between language and meaning, between language and truth, and much else besides. But across those disagreements there is a broad (not universal) consensus that that language is, in a way as yet unclear, the singularity that makes us what we are. This intuition aligns with the idea that the advent of language around 50,000 years ago coincided with arrival of behavioural modernity: that language was the moment that brought us recognisable homo sapiens.

I start with all this to make clear my allegiances. My interest in virtual worlds comes via a foundational idea, which is that language makes the human mode of being possible. Or, as the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor argues in The Language Animal, that language is the human mode of being.

That final clarification is important. It is to say that language doesn’t simply allow us to describe reality as we experience it. Rather, it actively constitutes those experiences — it brings into being the everyday world for us: a world of tables and chairs, cats and dogs, planets, Great Aunt Jemima, and so on.

This is a strange sounding idea, and it needs to be supported. We’ll come back to it in more detail later. For now, though, we need to move on to another implication of our status as the language animal.

(ii)

The idea that we humans are the language animal is associated with an even deeper conception of ourselves and our relationship to the world. One so deep, in fact, that it’s often hard for us even to see.

That is, that we humans are conscious agents, or subjects, looking out to a world ‘out there’, the object of our gaze.

This subject/object framework is at the heart of the western intellectual tradition. Most of all it has underpinned metaphysics: our quest to understand the true nature of reality. That’s because our belief that we are subjects looking to a ‘world out there’ makes the true nature of the world a problem for us. What is the underlying fabric of this world, the really real? How can we distinguish it from mere appearance?

In Ancient Greece, this quest for the real came to centre around a particular version of these questions. What does it mean for something to objectively exist?

Via different arguments, both Plato and Aristotle came to similar conclusions. In a world that is always in flux, they said, underlying reality is constituted by what persists – what remains present – over time. And what exists most of all is that which remains present eternally. Plato believed that ultimate reality consisted of a set of Ideal Forms; ideas that existed in a transcendent realm, from which we took the concepts we used to sort and label our everyday experience. Individual horses come and go; they cannot form a part of reality in its most ultimate sense. That ultimate reality, though, is in part constituted by the Form of a horse, which exists transcendentally and forever. Given the way it associates ultimate reality with persistent presence, this set of ideas is known as ‘the metaphysics of presence’.

Today, we don’t believe in a higher realm filled with the Forms. But later on, we’ll come back to the way in which this belief emerged out of fundamental facts about the nature of language. And we’ll see how those same facts fuelled the emergence of a set of more familiar spiritual beliefs: the Axial Age monotheistic religions.

The subject/object framework took on its recognisably modern shape with Descartes, who argued that there are two fundamental types of being in the world: mind and matter. According to Descartes, we are mental (or spiritual) beings looking out to a physical world. This worldview fuelled the scientific revolution, and continues to underlie it; it is echoed by the contemporary view, shared by most of us, that we are conscious agents looking out to a universe made of atoms. On this view, the underlying nature of objective reality is matter and energy.

As we all know, the natural sciences we’ve constructed on top of this framework have brought us to an unparalleled dominion over the Earth. But the modern subject/object framework leaves in place fundamental questions that continue to haunt us. If we (including our brains) are made only of matter, then how is that we seem to have mental, or conscious, experiences? What is it in our bodies that persists over time? If nothing, how can I be said to be the same person last year as I am today? Do the values I hold exist objectively, in the ‘world out there’? If not, then doesn’t that mean those values are not real?

In the early years of the 1920s, these questions troubled the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. He believed that their seeming unsolvability pointed to a deeper truth. These questions, said Heidegger, were mistakes, because they were founded in a mistaken view of our fundamental relationship with the world: the subject/object framework.

It’s not true, said Heidegger, that at heart we are subjects looking out to an independent and objective world. Instead, the underlying truth about our existence was our inescapable unity with the world, which Heidegger called being-in-the-world, or Dasein. To be human is to awake into being-in-the-world; to awake, that is, into a grappling with the world around us in order to serve our needs: survival, order, social connection, and so on. In that grappling, which Heidegger called engaged agency, we do not exist as a subject acting on a separate and independent set of entities that is ‘the world’; rather, we exist as an event, or process of action, that encompasses both self and world in a unified whole. All that we can have grounded knowledge of, says Heidegger, is that unified whole; it is the primordial fact of our being. The subject/object framework, he says, only comes about when we step back from that being-in-the-world and analyse it. Subject and object are theoretical constructs, and they are built on top of the more fundamental truth that is Dasein.

Heidegger favoured analogies based on tools and manual labour. To illustrate the idea of Dasein, he asked his readers to consider the experience of using a hammer. What is primary about that experience, said Heidegger, is my engaged agency with the hammer; is the process of hammering. That situation only dissolves into apparently constituent parts, into me and hammer, when I am caused to step back and reflect on it. That turns the hammer from what Heidegger called ready-at-hand – that is, unified with me in a process of engaged agency – to merely present-at-hand: an entity modelled as an independent object, part of an objective ‘world out there’.

Dasein was Heidegger’s fundamental idea; the concept that underpinned the rest of the philosophical system he began in Being and Time. And via this idea, the metaphysics of presence was dismissed as one long mistake: a series of conundrums and their attempted solutions based on the false idea that what is primary about our being in the world is subject/object.

Heidegger’s collapse of the subject/object framework proved one of the most influential – and controversial – ideas in all philosophy, and fuelled his reputation as one of the 20th-century’s most significant philosophers. His work helped create a schism in the discipline that still exists today: between continental philosophy on the one hand, and analytic on the other. In the analytic tradition – more commonly practised in the US and UK – Heidegger was ignored, or dismissed as a pedlar of obscure mysticisms. But on the continent the idea of Dasein exerted a vast influence on nearly everything that followed, providing the foundations first for existentialism and then for various forms of post-modernism. Meanwhile, Heidegger’s thinking also helped shape contemporary literary theory, psychology, and theology. All this while the reputation of Heidegger the man was damaged beyond repair by knowledge of his support for the Nazi regime; a powerful reminder that deep philosophical insight can be allied with a broken, repugnant politics.

Today, the wall that separates continental from analytic philosophy is not as high as it once was. Thinkers that bridge the two traditions, such as Charles Taylor, continue to build on the foundations Heidegger laid.

There is a small and growing literature that seeks to examine VR through the lens of Heidegger’s thinking.

It’s that avenue of thinking that I want to head down in what follows. As I’ve made clear, it seems to me that the emergence of virtual worlds can allow us to see with fresh eyes something true, something more authentic, about our relationship with this world.

We need to go on that journey step-by-step. And the next step is to ask: if Dasein is the primordial state of affairs for we humans, then how did we end up convinced that we are subjects looking out to an object world out there? Where did the subject/object framework come from?

That’s where we’ll take up this story when I send instalment two of this essay.

But a sneak preview of what lies ahead: the answer I’ll give is language. Language itself is the radical disruption that severs us from Dasein. This has radical consequences for our understanding of virtual worlds. Because when language estranges us from Dasein, it starts us out on a journey that finds its fullest realisation in VR.

But now I’m getting ahead of myself. I’ll be back soon.

Thanks for reading the first instalment of The Worlds to Come. It has concluded part way through Part 1 (I know, awkward, but hey). The next instalment will be in your inbox in the coming days.