Welcome to this essay from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and our shared future by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 20,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

🙌 This is instalment two of The Worlds to Come, an essay from NWSH. Go here to read the first instalment, or here to listen to it in podcast form. 🙌

It’s been a while

Earlier this year I published the first instalment of an essay, The Worlds to Come.

I promised the second instalment would follow quickly. That was months ago. So this email starts with a simple message: sorry for the delay. And to all those who wrote to ask, ‘where is part two of that essay?’, thanks for keeping the faith.

What happened? In short, life happened. This newsletter was born in the depths of the pandemic; I had time on my hands. But in the first quarter of this year other commitments — including my speaking schedule — accelerated back to full speed; it caught me off guard. I’m sure many of you can relate.

Still, in the grand scheme this is a small bump in the road. Writing to you every week is a huge privilege, and I love the community we’re building together and this journey we’re on to make sense of our shared future. This newsletter remains at the heart of my plans.

I’m going to send a note soon on what to expect from NWSH in the coming months, including a plan for longform essays and the return of the shorter notes that I used to send on Sundays — I really miss writing them.

But for now, here is the second instalment of The Worlds to Come.

This essay

This is an essay about systems of representation, virtual realities, and the way we understand our place in the world.

As a reminder, it’s not the typical NWSH fare. This essay is longer and more involved, but I hope also deeper, than the weekly updates. It’s an attempt to think with philosophy about virtual worlds and their implications for our orientation to this world.

Still keen to read? To refresh your memory, here is the table of contents for the whole essay:

Introduction: On the Threshold

1. What We Have Forgotten. Humans, language, and being-in-the-world.

2. Cast Adrift. A brief history of the Gods we made, how we banished them, and where that left us.

3. Crossing Over. Virtual worlds and the leap back to enchantment.

4. Conclusion: Where Next?

The instalment you’re reading will complete Part 1, leaving Parts 2, 3, and 4 still to come. Yes, this piece of work is better described as a short book than an essay. When it’s finished I’ll put the instalments together and publish the complete text as an ebook.

Given the time elapsed since I published the first instalment, let’s start with a brief recap.

Instalment One: a recap

If want to read first instalment in its entirety, you can find it here in text form and here in podcast form.

But a short recap of that instalment follows:

Introduction:

At the heart of this essay is a single idea: that our coming journey into virtual worlds can cause a transformation in our relationship with this world; one that can allow us to overcome nihilism, and again understand our lives as meaningful.

On first hearing, this claim seems impossibly far-fetched. I don’t believe that we’re set to disappear into the metaverse and live happily ever after. Instead, my interest lies in what virtual worlds can show us about this world and our relationship to it.

Specifically, I want to examine a set of more-or-less obscure relationships between virtual worlds, systems of representation, and meaning. My contention is that when these relationships are unpacked, virtual realities are shown to be the fullest realisation, or telos, of a certain orientation to the world: one that is mistaken, but that predominates among people who live inside modernity. And that because of this, our entry into virtual worlds can help us overcome that orientation and discover one that is more authentic.

Part 1: What We Have Forgotten

We humans are language animals. Aristotle calls us zōon logon echon: the animal that seeks meaning, the animal that speaks.

That idea is associated with another. That is, that we humans are subjective agents looking out to an external world, or a world-out-there. This idea, which we’ll call the subject/object framework, is embedded so deep in the heart of western metaphysics that it’s sometimes hard for us to see it. It underpins the modern scientific worldview, which sees us as conscious beings looking out to an external world made of atoms and energy.

In the early 20th-century, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger attacked the foundations of western metaphysics by exploding the subject/object framework. It’s not true, said Heidegger, that at heart we are subjects looking out to an independent world-out-there. Instead, the underlying truth about our existence is our inescapable unity with the world, which Heidegger called being-in-the-world, or Dasein.

Heidegger’s collapse of the subject/object framework proved one of the most influential — and controversial — ideas in all philosophy. It sought to overturn traditional western metaphysics, depicting that discipline as one long mistake: a series of conundrums and their attempted solutions based on the false idea that what is primary about our being in the world is subject/object.

Today, philosophers continue to build on the foundations Heidegger laid. There is even a small and growing literature that seeks to examine VR through the lens of Heidegger’s thinking. It’s that avenue of thinking that I want to head down in what follows.

We need to go on that journey step-by-step. And the next step is to ask: if Dasein is the primordial state of affairs for we humans, then how did we end up convinced that we are subjects looking out to an objective world-out-there? The answer I’ll give is language. Language itself is the radical disruption that severs us from Dasein. This has radical consequences for our understanding of virtual worlds. Because when language estranges us from Dasein, it starts us out on a journey that finds its fullest realisation in VR.

1. What We Have Forgotten (cont…)

(iii)

When we come to understand ourselves as subjects looking out to an objective world, the unity of self and world — of Dasein — is broken. We become a disengaged ‘knower’, who must try somehow to hook up to and have knowledge of the ‘world out there’.

This is an estrangement from the underlying truth (as Heidegger would have us understand it) of self-world unity. How does this estrangement come about?

Heidegger’s answers were complex. Essentially, he believed that we become estranged from the truth of Dasein when something causes us to step back from our engaged agency and try to analyse it. That can happen when our engaged agency is interrupted by some error or fault — when, to return to our earlier example, the hammer that we are using breaks and our hammering comes to a sudden end.

What lies submerged in Heidegger’s analysis, though, is a deeper and more radical answer. It is that language itself is at the root of the processes that sever us from Dasein.

This, I should admit, is a controversial reading — some might argue a misreading — of Heidegger. It does have roots in his thinking: he writes a lot about how the misuse of language is one of the processes that estranges us from Dasein and establishes the subject/object framework. But he also says that ‘language is the house of Being’, which has widely been interpreted as meaning that language and Dasein are bound together. Overall, Heidegger’s beliefs on the relationship between language and estrangement from Dasein remain somewhat opaque, and are the subject of ongoing debate.

So why do I contend that language is the driver of our estrangement? First, we need to remember what this estrangement consists of. Dasein, or our being-in-the-world, constitutes a fundamental unity between self and world: a me-world. In that state of affairs we don’t hold the world apart from ourselves and examine it at a distance. Rather, we are one with it in a process of engaged agency. We know a hammer not as an independent and objectively-existing object, but as part of a network of meanings that taken together form our understanding of and grappling with the overall scene.

But the stance we take towards the world when we become language-bearers is, it seems to me, antagonistic to all that. The very fact of having the word hammer necessitates, already, a framework in which there is me and the hammer — it necessitates a break from the me-world, and the establishment of a subject/object framework that underpins our conception of the world-out-there.

I contend that it is the event of language that is the break point. That is, language is what severs us from the primordial oneness that is the me-world, and establishes the subject/object framework that creates, for us, an externalised world-out-there (which we typically call, simply, the world).

What can we find in Heidegger to support this idea? Heidegger’s thinking on the way we know a hammer, or anything else, involves a tripartite model of ‘primary understanding’ that he calls fore-structure, fore-having, and fore-conception. He seems to believe that aspects of this understanding are pre-linguistic; that is, they do not depend on language. There are times when he gestures towards the idea that it is the event of language that breaks us out of primary understanding and into the subject/object model. But at other times he steps back from this. The moment of severance remains obscure.

What is more clear, though, is that Heidegger agrees that once the subject/object framework is established — whatever the cause — then language tends to further the estrangement from Dasein that this framework constitutes. Language causes us to crystallise our sense of objects as independent entities, uprooted from the network of relationships that renders them meaningful within Dasein. Language is the process that allows us isolate objects as objects, and hold them in our attention. It fuels our ability to exit engaged agency and instead undertake various forms of high-level theorising in which we become disinterested ‘knowers’ looking out to a world of independently existing entities. Heidegger refers to the ways in which language estranges us from the truth of Dasein when he talks about ‘idle talk’: language that immerses us in a theoretical, or inauthentic, versions of our being.

If we come to believe that language enacts our estrangement from Dasein, then we can see it as performing a strange and paradoxical double function. Language at once constitutes the human mode of being, and yet estranges us from that being in its most fundamental form. And because language is the very medium in which our thinking on this matter takes place, the ways in which language performs this paradoxical quality must remain mostly opaque to us. As language-bearers trying to understand the impact of language on our mode of being, we are like fish trying to understand how it feels to be wet.

We might, then, come to believe that language is best understood in the same way that physicists understand a singularity. That is, as an object at which the laws that govern our understanding of the world break down. It’s my contention that this is just how we must understand language. As the singularity at the heart of our being.

The idea that language estranges us from some deeper, primordial connection with the world is far from new. The 20th-century philosopher Ernst Cassirer, who spent a lifetime analysing symbolic representation and systems of meaning, believed that our experience of the world comes via symbolic systems that interpose themselves between us and reality:

‘No longer can man confront reality immediately; he cannot see it, as it were, face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves, man is in a sense constantly conversing with himself.’

Nietzsche said ‘words brutalise’. The primitivist philosopher John Zerzan argues that ‘language may be properly considered the fundamental ideology, perhaps as deep a separation from the natural world as self-existent time.’

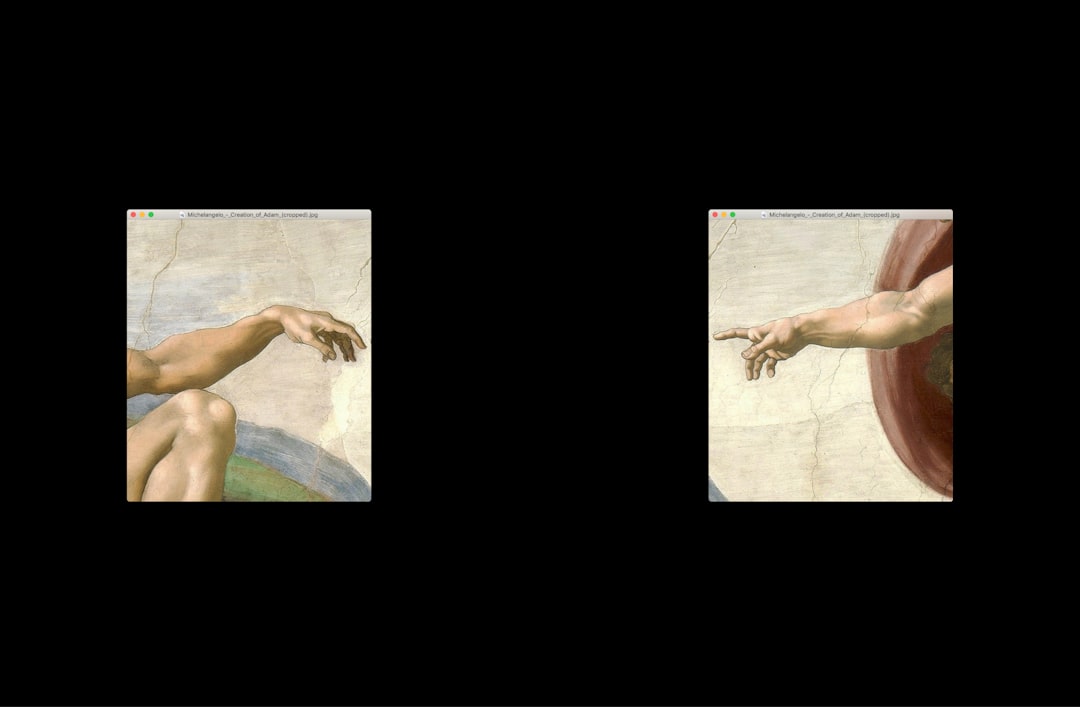

Meanwhile, latent in some of the oldest stories in our culture is the idea of language as a deep form of estrangement.

When God banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, he also banished them from the original, Adamic language. To leave the Garden was to forget the language of God; the ur-language that gives everything its proper name. Instead, we are cursed to use false languages of our own making — to use artificial words that do not truly refer to the world.

At the heart of European culture’s ultimate origin story, then, is a message about our estrangement from the world, and the role that language plays in that estrangement.

The Edenic harmony we’ve forgotten, and the right language associated with it — is it best understood as Dasein?

(iv)

We have travelled a long way from our central concern: virtual realities. But the terrain we’ve covered has deep implications for the emergence of virtual worlds and their impact on our relationship with this world.

Share this post